Elections and Markets

As we enter the final months of 2022, we are greeted with yet another election cycle. This version, much like its predecessors, has led to an increase in client inquiries about market ramifications relating to the results.

We previously wrote about elections and markets back in October of 2020, and a lot of what will be outlined here is very similar. This includes the beginning where we mention that the results of the elections are never known until all of the votes are tallied. Predictions of results are exactly that, predictions.

In the short-term, both leading up to election night and the weeks after, we will likely see markets doing their usual whipsawing. Some people will inevitably use the election as reasoning, but that’s probably not the biggest factor.

In late September we wrote to you informing of current market conditions, which at the time were pretty grim. There were two primary factors at play that had led to a steep drawdown: higher-than-expected inflation, and a large increase in interest rates. As we noted at the time, markets not only have current conditions priced in, but the expectations of what is to come in the months ahead.

Since that post the economic conditions have not exactly improved, yet we have seen U.S. markets rally by about 7%. Furthermore, small and value companies have seen returns in excess of 10%.

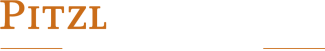

There are many individuals who credit the upcoming election with this recent rally. PredictIt, which is a public market that trades shares of expected results, saw a flip in the odds of senate control over the past 30 days.

If we isolate that single factor, it could be easy to infer that this flip in forecasted election results has been the primary factor in the stock market turn.

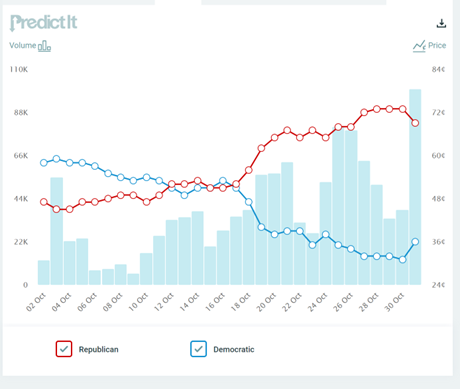

However, it’s also just as easy to infer that McDonald’s announcing the return of the McRib has had the same effect. Shockingly, the presence of the McRib on the McDonald’s menu has resulted in market returns massively greater than when it is not available. Since the announcement of its return we have seen a stock market increase of 3%.

All kidding aside, you can make a lot of short-term inferences based on any information you want. But when it comes to elections markets tend to not care as much, especially over long periods.

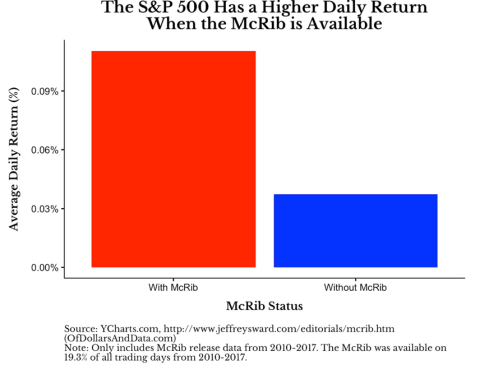

The chart below illustrates how the S&P 500 has performed based on congressional control. There are small periods you can pick to make an argument on performance based on one party or the other. However, I have a tough time finding anything in there that is blatantly obvious.

The term “market” gets thrown around very freely. So much so that it can often be easy to forget exactly what a market is. It’s important to remember that, at its most basic level, a market is just a large collection of companies and businesses. When you are investing your money in markets you are investing in businesses, not political parties.

We’ve written and discussed this in excess before, but companies are living and breathing things. Their primary goals are to survive and grow. Some of the leaders in these companies may have a personal political agenda, but at the end of the day the company itself doesn’t care who’s in the White House or has control of congress. They simply adjust and adapt to whatever changes may come as a result.

It is our belief that the more important short-term factors are still interest rates and inflation, which at this point have become obvious partners in crime. Historically this has been the case, with inflation being the main character and interest rates being the trusted sidekick keeping them in line.

Now on the surface this appears to still be the case, and the Federal Reserve is still acting as if this is the case. However, there is a lot of recent thinking and research stating that the main character may actually be flipped.

In prior periods of high inflation, the prevailing theory was that raising interest rates would slow the movement of money. The reason that people and companies borrow money is to spend it. If that money becomes too expensive to borrow (meaning too high of interest rates) they will opt not to borrow, and thus not spend. When spending is reduced the inflation rate would start to fall. Once the inflation rate got to a more comfortable place then the Fed could consider raising interest rates again. Rinse and repeat.

The past 10 or so years has started to see a shift in economic thinking. A growing minority of economists are starting to believe that higher interest rates actually leads to higher inflation. The prevailing theory behind this is that companies put a high premium on protecting their margins. If they are now required to pay higher interest rates to borrow money they will simply pass the extra expense on to consumers. This will lead to a higher cost for products/services, which is the textbook definition of inflation.

So which of these theories is correct? In truth, it’s more than likely somewhere in the middle. This can best be demonstrated by the difference in mortgage rates from the last two years.

Back in 2020, in the heart of the pandemic, we were helping a lot of you refinance your homes. Many of you were able to lock in sub-3% mortgage rates for the next few decades. Think about that, you are able to borrow hundreds of thousands of dollars, for decades, at only 3%! A 30-yr U.S. government bond is currently paying 4.13%. If you had the cash available to pay off your newly refinanced mortgage, you would earn 1% more by handing the government your money for the next 30 years.

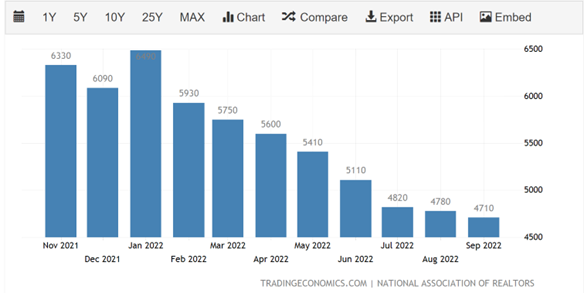

On the flip side, over the past 10 months we have seen the 30-yr mortgage rate climb to over 7%. This has led to home sales coming to a screeching halt. The chart below provides data on existing home sales on a monthly basis, which have seen a steep drop-off since the start of the year.

Something here has to give, and based on news over the past few weeks it seems like the tides are changing. National banks around the world have started to ease their interest rate increases, and have made calls for the U.S. to do the same. It’s estimated that foreign countries/investors own roughly 25% of all U.S. debt. As we’ve risen rates these countries ownership of our debt has been negatively affected.

It was announced yesterday that the Fed would be raising interest rates by another .75%. It was fairly well known in financial circles that this type of increase was coming, and markets were well prepared for the news.

What came as a bigger surprise is Fed Chairman Jerome Powell expressing a continuation of using interest rates to fight inflation. The consensus thinking was that we would have a .75% increase in November, and then a .50% or lower increase in December. After his remarks yesterday the December expectation is a lot less certain.

However, between now and the December decision we will receive two different inflation reports. If these readings fall back to a more normal level, which would not be a huge surprise, we may see the Fed opt to increase at smaller increments. If this indeed does happen we will likely see markets continue their rebound.

On the other hand, if they continue to push the higher rates narrative we could see a continued struggle.

Every market cycle comes with its own unique combination of factors, but the individual factors have almost always been there before. This is not the first-time markets have experienced an election, been through high inflation, or seen interest rates rise. The combination of any given factor always affects the short-term market performance, but not the long-term. Markets, and the underlying companies, always have long-term growth and survival on the front burner. These factors don’t eliminate those goals.

As always, we are here to help answer any questions or concerns. Please do not hesitate to reach out.